There’s a brewing storm around carbon offsets. They’re being used to protect trees that nobody wanted to cut down, fund wind turbines running for the last 10 years, and build new solar panels that were going to be built anyway. Some companies are deliberately increasing emissions in order to be paid for decreasing them again.

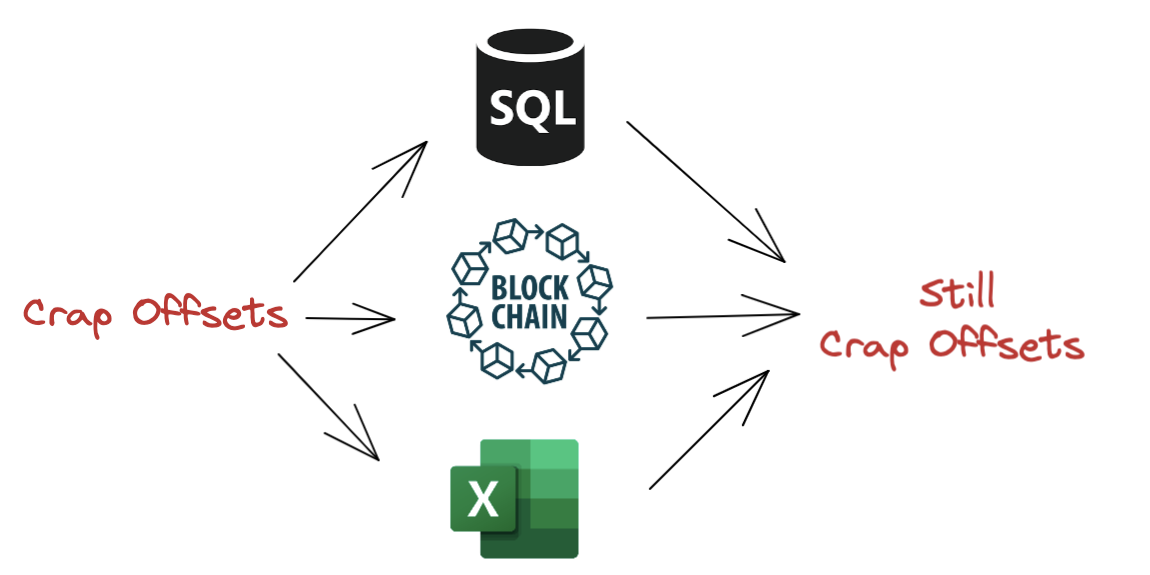

What solves absolute none of these problems? Blockchain!

Blockchain solves a data problem that doesn’t exist

In theory (though perhaps not in practice), blockchain provides a distributed ledger which is difficult to muck around with. Transactions are hard to fake, and so you can trust that whoever the blockchain says owns an offset really owns an offset. There are a bunch of companies purporting to bring the bright cleansing sunlight of blockchain to the rotten world of carbon offsets.

Unfortunately, blockchain provides a solution to a completely different problem. None of the issues with offsets relate to people falsifying transactions, or malevolent actors manipulating database records. The big sellers of offsets are not struggling to keep track of their tiddlywinks. Just like the rest of the financial system, they use fairly reliable, cheap, well understood database technologies to store data. It’s not very interesting. It’s also not a cause for concern.

Garbage in, garbage out

All of the problems with carbon offsetting relate to verifying something has happened, or not happened in the real world because you spent some money 1.

Bogus offsets arise when people misrepresent the state of the real world. Whether they then write that dodgy data into an SQL database, blockchain, or onto a stone tablet doesn’t make the slightest bit of difference. As we’re fond of saying in data science, it’s garbage in, garbage out.

The actual problems plaguing carbon offsets can be clustered into two overarching challenges:

The easy problem: what is the current state of the world?

You can find this out if you have an incentive to do so (spoiler: most buyers of cheap offsets do not). These are questions like:

- is there more carbon in this soil than there used to be?

- have these villages really switched to clean cookstoves?

- are the trees I paid for still standing?

Sometimes it can be tricky to figure these things out, but there are tangible answers to those questions. Startups like RegrowAg, Pachama, and Yardstick are trying to bring down the cost of observing of the world and checking it lines up with what it says on your offset certificate 2.

The hard problem: what would the state of the world have been?

Many dud offsets correspond to projects that would have happened regardless of whether the offset was sold. The opposite is also a problem: offsets “preventing” events that were actually never going to occur. To tell whether your offset made a difference, you need to know things like:

- would this forest have been chopped down if it weren’t for my offset?

- would this hydroelectric dam have been built if it weren’t for my offset?

- would this gas have been leaked into the atmosphere if it weren’t for my offset?

Unfortunately, there’s no conclusive answers to these questions. They’re statements about worlds that do not exist; futures that never came to pass. To my knowledge, nobody has a clever startup working on answering these questions, probably because they’re very hard and any viable solution would be too complex for anybody to trust.

CDR solves all of the problems with offsets

Last week saw large amounts of money committed to Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR) projects by the Frontier Fund ($1bn of guaranteed purchases led by Stripe with participants including Alphabet, Meta and Shopify) and Lowercarbon Capital ($350m of funding for removal startups).

CDR involves paying somebody large amounts of money to actively remove carbon dioxide from the air and store it somewhere permanently. Advocates of CDR point to IPCC modelling which shows that under even the most optimistic scenarios, we’re going to have to remove large quantities of carbon from the atmosphere. That’s totally true, but another reason climate-conscious big corporates are excited about CDR is that it solves all of the informational problems associated with offsets 3.

Popular companies in the space include Charm Industrial (”making oil and putting it back underground”), Climeworks (”sucking carbon out of the air”) and Heirloom (”using baked limestone to soak up carbon”).

What all of these wacky sounding projects have in common is that it’s relatively easy to ascertain how they’ve impacted the world. It’s much easier to track how much oil you’ve made than monitor a rainforest’s carbon content. Even more importantly, you can be damn well sure that these barmy projects weren’t going to happen if you weren’t paying for it. They’re reassuringly expensive – about $300 per tonne of CO2 according to this analysis.

They therefore solve the hard problem of offsets: in the alternative world where you didn’t pay for that tonne of CO2 to be sequestered, it didn’t happen.

How many of these new CDR projects rely upon blockchain?

Erm, none.

Update 3rd May 2022: Carbonplan wrote a fantastic deepdive – Zombies on the Blockchain – about blockchain schemes resurrecting garbage offsets which were previously unsellable. Thanks to Michael Skaug for the link.

Please reach out if you feel like I’ve got this wrong and can explain why. I have tried to be open minded when engaging with these climate-blockchain projects but every explanation I’ve received doesn’t make sense to me and leaves me with the icky sensation that somebody is trying to profit from my confusion.

Footnotes

- These problems are often categorized as ones of leakage (did the carbon get emitted elsewhere instead?), additionality (did the offset change the amount of carbon that would have been emitted), and permanence (did the carbon stay emitted?)

- CarbonPlan also do fabulous work assessing the quality of offsets: check out this gorgeous report on overcrediting in Californian forests

- More skeptical environmentalists might also observe that the reason VC’s are so excited about CDR is that it seems likely that there will be a few big players which become very dominant in the space. These oligopolies will end up earning outsized returns compared to less technologically uncertain ways of cutting carbon like wind and solar. I think this is accurate and also fine, if it means we remove huge quantities of carbon.