The late Sir David McKay was a giant of the machine learning and energy communities. Renowned for the sharpness of his wit and the clarity of his communication, he served as the Chief Scientific Advisor to the UK’s Department of Energy & Climate Change from 2009 to 2014. He was a professor at Cambridge until his untimely death in 2016.

One of his most enduring contributions was the iconic Sustainable Energy Without The Hot Air, commonly referred to by practitioners (including my girlfriend) as “the bible” of quantitative work in the field. Sustainable Energy Without the Hot Air, or SEWTHA as it’s fondly known, brought a “numbers not adjectives” lens to the heated discussions around England’s energy supply and demand, plotting several courses forward which balanced the needs of suppliers and consumers whilst respecting the laws of physics.

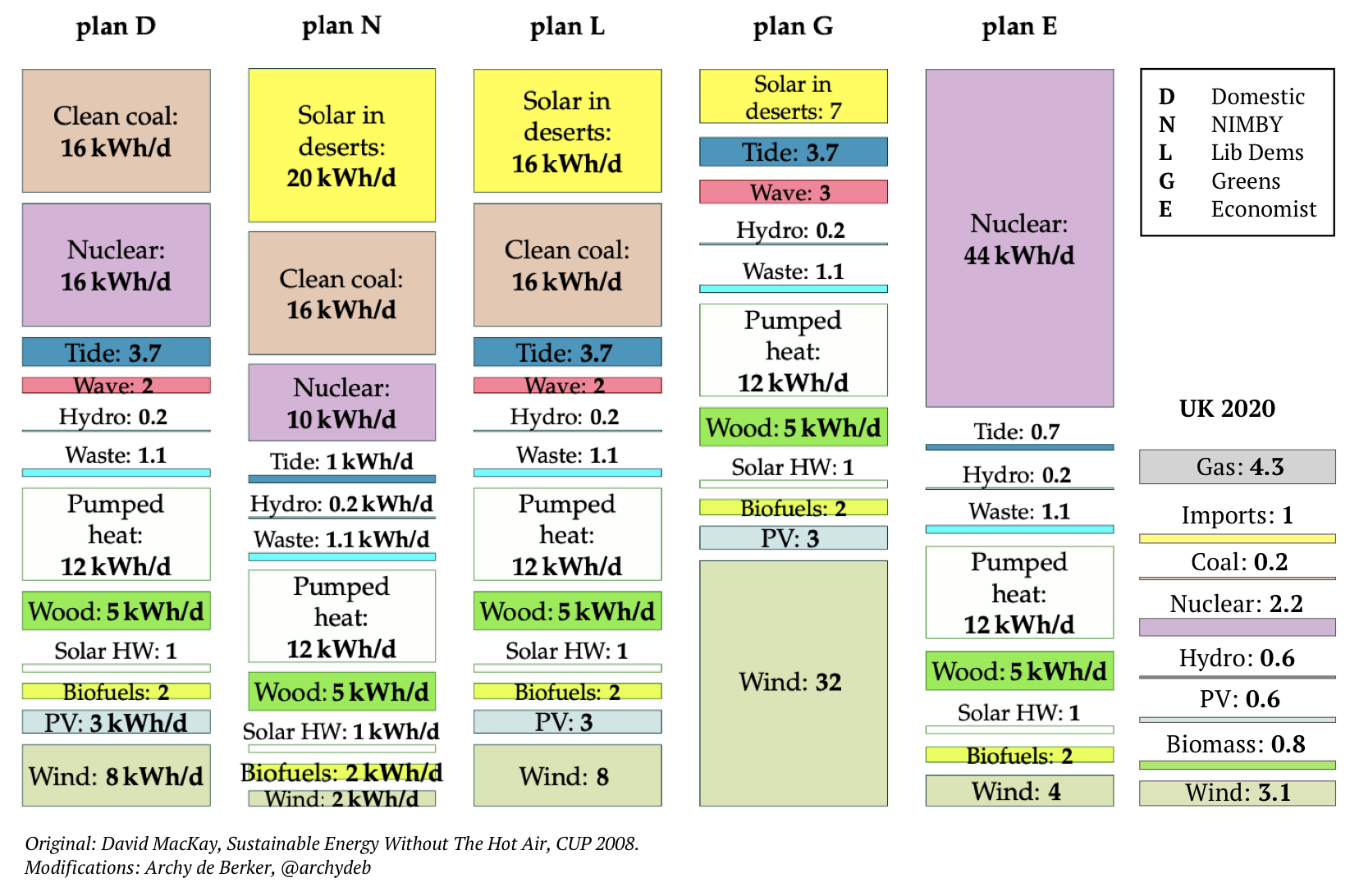

SEWTHA concludes with 5 possible plans that add up for providing carbon-free energy for the UK. I was curious to see how we were getting on in the decade or so since the book’s publication, so I grabbed some generation data from the National Grid ESO and stacked it up against MacKay’s 5 scenarios.

MacKay’s 5 plans

MacKay’s plans all achieve full decarbonization of energy production, and aim to hit a hypothetical tripling of electricity demand driven by electrification of heating and transport. The numbers are in kWh/day/person, an unconventional unit used throughout the book to help the reader build an understanding of how their consumption fits into the UK’s total.

The 5 plans are lettered as follows:

D: Domestic Diversity. Prioritizes generating all of our energy in the UK, from a diverse array of sources.

N: Not In My Backyard (NIMBY). Limits land use for renewable energy in the UK, preferring imports.

L: Resembles the Liberal Democrat’s plan in 2008.

G: Resembles the Green Party’s platform in 2008 – notable lack of nuclear.

E: Economist’s plan: the cheapest option.

MacKay’s plans vs Britain in 2020

1. Total generation has a long way to go

MacKay estimated that electrification of heating and transport, we’d need to more than triple energy generation to around 50 kWh/day/person. In GW terms, this equates to 125GW of energy production. We’re currently at 103.1GW installed (source), but the capacity factor of many of those assets is low (the capacity factor is the % of possible capacity that actually gets generated).

This means that in terms of actual energy produced, we’ve got some way to go. Current electricity generation sits at about 12 kWh/day/person. Since the vast majority of transport and heat remains unnelectrified, this isn’t surprising: the demand doesn’t justify generating so much energy.

2. Coal is dead

The UK has done a spectacular job of weaning itself off coal, from a peak contribution of 42% in 2012 to less than 2% in 2020.

“Clean coal” (coal power with capture and storage) is no longer a topic of discussion. Instead, we’ve seen the rise of gas power. Gas is cleaner than coal (about 1/2 of the emissions), but it’s still not clean.

Real world deployment of carbon capture and storage has been sluggish. The UK plans to pilot 2 carbon capture clusters by the mid-2020s. My understanding is that the staggering fall in the cost of renewables has made expensive carbon capture projects even less economic than they were in 2008.

However, every scenario in which we meet the goals of the Paris agreement still involves substantial deployment of Carbon Dioxide Removal technologies. I suspect that in the UK these will end up playing a more central role in hard-to-decarbonize industries such as steel and fertilizer production than in energy.

3. Wind is winning

We already have more wind power than MacKay allows for in his NIMBY scenario!

Wind is a UK success story. The cost of electricity from wind has fallen by more than 70% since 2008, and UK capacity has increased from 5.4 GW in 2010 to 24 GW in 2019 (source).

This growth is projected to continue, largely driven by sustained investment in off shore wind. Rystad Energy estimate that offshore wind will almost triple from 2020 levels by 2026. That’s 20.7 kWh/person/day, or ~2/3 of the way to MacKay’s wind maximum.

SEWTHA is as relevant as ever

I started this piece with the intention of updating MacKay’s numbers for wind and solar, hoping to show that a renewable future was more practical than it has seemed in 2008.

In fact, SEWTHA has aged well, because MacKay was careful to avoid proposing plans based upon economics. His analysis is largely based upon physical limits upon efficiency in solar and wind power, and the space and natural resources available in the UK.

Although the price of wind and solar has dropped spectacularly, their efficiency hasn’t changed that much. Those hard limits on energy and space remain. We’ve got a large and windy coastline, but even if we devoted a colossal 1/3 of it to onshore wind, we’d still only meet 64% of our energy needs (this is MacKay’s Plan G)! This is a sobering conclusion, and I’m not aware of anything that’s changed in the last 13 years which challenge its validity.

We’ve come a long way, but we still have a truly epic task ahead of us.

So where will the UK’s extra energy come from?

Caveat: there are lots of people far more qualified than to answer this question (and if you are one, please let me know!).

From MacKay’s analysis, it seems like importing large amounts of solar energy remains the largest untapped source. The UK continues to build new interconnectors to Europe, which seems like a good thing, although to my knowledge they’re largely used to import French nuclear power rather than Spanish solar. Check out ElectricityMap for live analysis of the carbon intensity of energy flows in Europe.

Nuclear continues to receive attention in the UK, with the government’s 10 point plan for a green industrial revolution allocating ~£500m to research. This seems unlikely to yield many GW in the next 20 years 1.

Further reading

- If the 300+ pages of SEWTHA are intimidating, I’d really recommend reading the 10 page synopsis, here.

- The UK Government’s 10 point plan for carbon neutrality by 2050

- ElectricityMap’s live dashboard of UK energy generation and consumption

- National Grid‘s historic generation data, used for my graphs

If you like energy and data work, you might like this piece on orienting solar panels to meet UK peak demand. I publish new writing on Twitter.

Footnotes

- Bill Gates has been throwing money at this problem for the last decade without much joy, and he’s both smarter and wealthier than the government, so I don’t hold out much hope